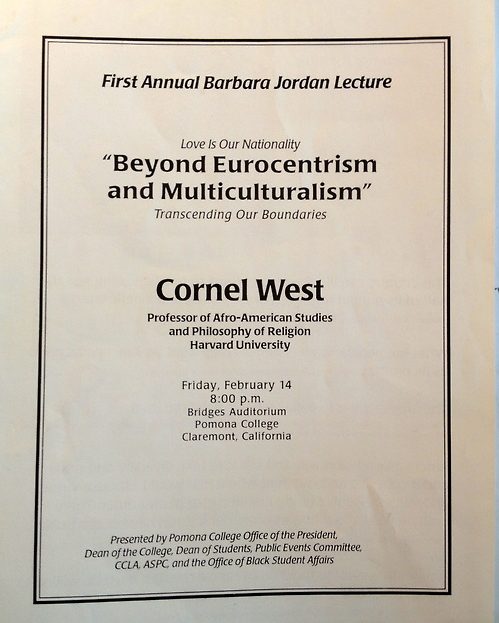

In February 1997, the fabulous African American religion scholar and public intellectual spoke at Claremont Graduate School. What a presence, with his purple velvet suit and his long figures that slowly rapped on the podium as he spoke. This was six years before his star turn in The Matrix. I seem to recall that he talked about the existential crisis and our inevitable future as “food for the worms.”

This wasn’t the first time I had heard West speak. He was a friend of one of my favorite professors at Gustavus, Dr. William Dean, and he came to campus during my junior or senior year. And it wouldn’t be the last time I heard him at one of the schools I was attending. In 2001, he spoke at Emory, where I was working on my Ph.D.. His speaking at all three of my schools says a lot about how much speaking he was (and still is) doing around the country.

During my masters, maybe after hearing this speech, I started to read more of his work, especially his thoughts on pragmatism, jazz and tragic hope. His discussions of tragic hope, risking identity, radical democracy and the new cultural critic were central to my thinking in my masters’s thesis and my dissertation.

In the concluding chapter of my dissertation, I referenced his ideas about continuing to act in the face of the uncertainty and fragility of “our democratic experiment” in the U.S.. I wrote:

The story of democracy within twenty-first century feminism is a story about hope and survival. It is a story in which we remember those individuals who were able to survive within the difficult, risky and uncertain practices of feminist democracy and who effectively resisted the system in many different ways. This is not a story exclusively about how those individuals were successful, but also about how they failed, yet kept persisting in their practices.

And added the following footnote:

Cornel West writes: “And if we lose our precious democratic experiment, let it be said that we went down swinging like Ella Fitzgerald and Muhammad Ali—with style, grace, and a smile that signifies that the seeds of democracy matters will flower and flourish somewhere and somehow and remember our gallant efforts” (West Democracy Matters, 218).

Among many of the philosopher professors at Emory (but not my advisor, who also worked with him), West wasn’t taken seriously. Why? I think it was because his work was too accessible and aimed at audiences outside of the academy. They claimed it wasn’t rigorous enough. Was this one of the official reasons why Larry Sommers, then president of Harvard University, fired him? My professors’ dismissal of West was another cue, one of many that I received over my years in higher education, that the academy and its industrial complex might not be for me.